Early - mid 18th century Highland dress

Chapter 2: Highland dress in the Gàidhealtachd (early – mid 18th century)

As argued in the introduction, there is a lack of information about female Highland dress which is why this dissertation is needed. In order to put the discussion on female Highland dress into some context, a discussion on male Highland dress (for which there is plenty of discussion in the literature) is first required.

Since the 1715 Jacobite uprising, tartan had become firmly associated with the Jacobite army despite the fact that a great number of Jacobite soldiers were not from the Highlands and the wearing of mixed tartans were very common. (Scott 2018: 18 & 23). A number of visitors to the Highlands had been made to feel uncomfortable by Highland dress as it subverted 18th century norms of the Western European male’s attire of an early form of the three-piece suit (Scott, 2018: 27).

Figure 1 : Morier, David (1745) An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745 (accessed from https://www.rct.uk/collection/401243/an-incident-in-the-rebellion-of-1745 on 28th May 2019)

Male Highland dress of the first part of the eighteenth century was visually vastly different to that of the rest of Europe. The majority of Britain at this time accepted that women wore skirts and men wore trousers, so the plaid – which is essentially a large rectangular piece of woollen cloth worn as a skirt- was in direct conflict with the rest of the country (Chapman 1995:8).

David Morier’s An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745 (Figure 1, above) was commissioned by the Duke of Cumberland a few months after the Hanoverian victory at Culloden, clearly as a celebration of his victory. The painting depicts the battle at Culloden and Morier used imprisoned Jacobite soldiers for his models (as well as British soldiers). The painting was given as a gift to Cumberland’s father, George II, and remains in the Royal collection and is on display in the lobby of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

Along with the blue bonnet and the white cockade, tartan clothing was seen as a part of the Jacobite ‘uniform’ – it had been worn by Jacobite soldiers in all Jacobite uprisings between 1689 and 1746- and not as an ethnic identifier (Pittock, 2010: locations 920-970/6575). That is was part of a uniform is made obvious from Lord George Murray’s orders of 14th – 15th April 1746 where he commanded that all Highlanders should wear kilts (Lenman and Gibson 1990: 226).

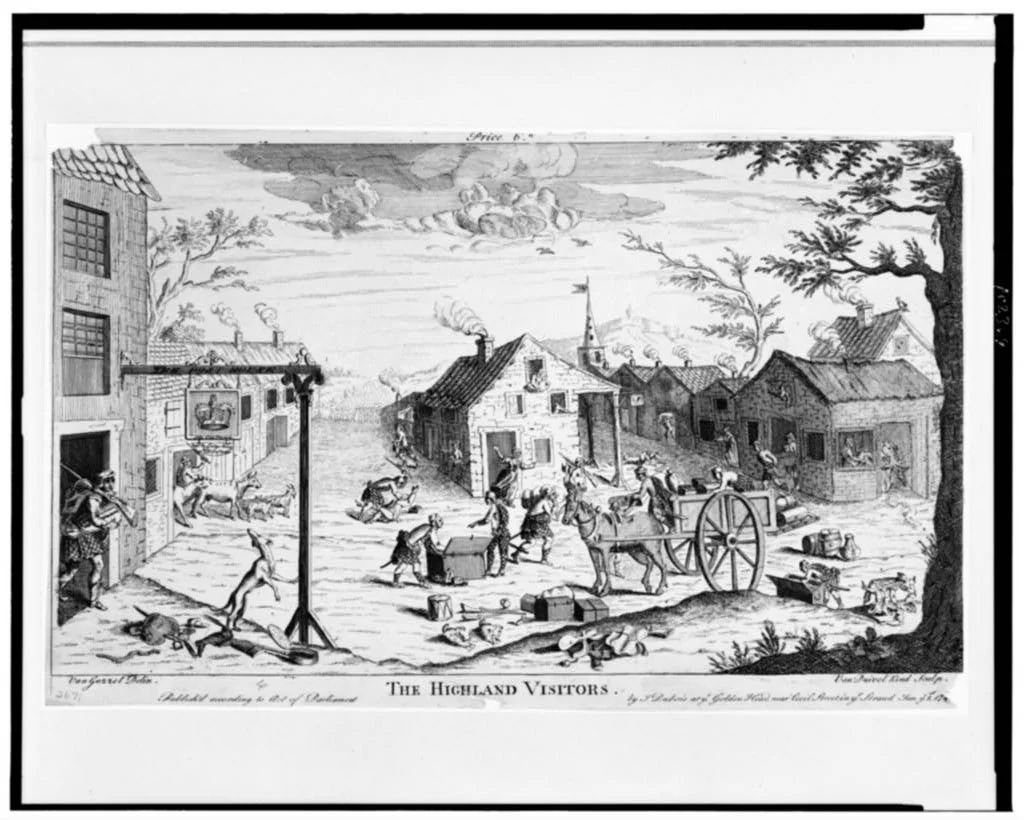

Figure 2: Van Duivel, Kind (1745) The Highland Visitors (accessed fromwww.loc.gov/pictures/item/91727491/ on 28th May 2019)

Jacobites in tartan uniforms were portrayed in English caricatures as thieving, lice-ridden savages who ate children (Craig, 2017) and who ransacked villages, murdered men and dogs, and raped women (figure 2). Highland dress was frequently parodied in both English satirical portraits of Highlanders and Prince Charles Edward, as well as used in plays on the London stage mocking Highlanders. A number of contemporary satirical engravings and etchings of the Prince was clearly designed to not only to mock him but also to mock Highland dress (figure 3), such as the ‘wanted poster’ etching from 1745 by Richard Cooper, the Elder.

Figure 3: Cooper, Richard (1745) Prince Charles Edward Stuart, 1720 - 1788. Eldest son of Prince James Francis Edward Stuart ('Wanted Poster') accessed from https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-andartists/37299/prince-charles-edward-stuart-1720-1788-eldest-son-prince-james-francis-edward-stuart-wantedposter?search=prince%20charles%20edward%20stuart&page=1&search_set_offset=107 on 28th May 2019)

The Dress Act, part of the Act of Proscription (19 Geo. II, c.39), came into force in Scotland on 1st August 1747. Section 16 of the Act made the wearing of “Highland clothes (that is to say) the Plaid, Philabeg, or little Kilt, Trowse, Shoulder-belts, or any part whatever of what peculiarly belongs to the Highland Garb; and that no tartan or party-coloured plaid of stuff shall be used for Great Coats or upper coats” by men and boys (other than those employed as officers and soldiers in the King’s forces) illegal with the penalty of the first offence six months’ imprisonment, or a second offence transportation to the colonies for seven years (19 Geo. II, c.39).

Up until this point, British sumptuary laws had been used to reinforce social hierarchies, but the goal of the 1746 Disarming Act (19 Geo. II, c.39) was to take away the symbol of the Highlanders’ methods of fighting (Lenman and Gibson 1990: 240).

Commanding Highlanders to give up a costume of which they were incredibly proud became a matter of personal shame (Dunbar 1981: 51). It is possible that a large number of men were arrested for wearing tartan in the few years following the enforcement of the Act of Proscription, but only a few are recorded in the literature on Highland dress, most comprehensively by Dunbar (1962 and 1981). Dunbar states that he could not find any evidence of the Act before enforced before 1748 but an Army order of December 1748 changed the situation (Dunbar 1981:51).

Highlanders who were under suspicion of being rebels were made to swear an oath and anyone caught wearing tartan should be taken to the nearest magistrate, in the tartan clothing, for trial.

The policing of the Act was not equally enforced across the whole of Scotland. The districts of Rannoch, Glencoe, Lochaber, Glengarry, Knoydart, Glenmoriston and Lagan in Badenoch had been chosen by the British in 1747 for ‘thorough supervision and disarmament’, but local magistrates and justices of the peace were as lenient as possible and accepted excuses for why the men had been found in Highland dress such as they were wearing women’s plaids, a plaid had been overdyed or a kilt sewn up the centre was actually a pair of trews (Grant and Cheape 1997:206)

In 1755, the Forfeited Estates Commission ordered a census to be taken on the estates it managed on behalf of the King (SRO 1973). Factors of the estates were asked a large number of questions to report upon, including ‘Whether the laws prohibiting the Highland dress have taken full effect in that Estate’.

The reports back to the Commissioners of the Annexed Estates , on the whole, stated that the ‘laws prohibiting the Highland dress’ had taken full effect with the exception of the barony of Colgach in the parish of Lochbroom:

‘The Highland Dress and Disarming Acts have taken effect here, tho’ perhaps not so fully as on the other parts of this estate, for many corners of this barony lye so remote & divided from each other that very probably some fellows may presume to transgress where they can do it with impunity as there are no troops quartered among them, but the factor is hopefull that they are now more upon their guard as he has published repeated advertisements of their danger’ (SRO 1973: 40)

The Government seems to have been reassured by the responses of their factors as by 1760 there were no longer any prosecutions for wearing Highland dress due to patrols being stopped and the proscription being relaxed (Dunbar 1962: 8).

The Dress Act never applied to two groups of men: the military and the gentry.

The use of tartan by the British military is a fascinating subject which is too broad a subject to discuss here, except to mention that it was rather ingenious to allow Highland regiments that fought in the Seven Years War in North America to wear a tartan uniform when it was still proscribed in the Highlands. For example, the Fraser’s Highlanders regiment was formed in 1757 to fight in North America and their uniform included diced tartan hose, a traditional plaid and blue woollen bonnet (which all could arguably be described as ‘traditional’ Highland dress) along with a short redcoat.

Figure 4: Mossman, William (1749) John Campbell of the Bank (accessed from https://www.rbs.com/heritage/people/john-campbell.html on 29th May 2019)

During the period of proscription, a large number of the gentry had portraits of themselves painted wearing tartan. John Campbell, who was the main cashier at the Royal Bank of Scotland in Edinburgh, curiously had a portrait of himself painted by William Mossman in 1749 (figure ). Although Campbell’s political affiliation is not known, it seems likely to assume that he may have been a supporter of the Jacobites due his aiding them to trade RBS bank notes for gold during the Jacobite occupation of Edinburgh in 1745. In the portrait, not only is Campbell wearing Highland dress, but he is also fully armed. This therefore begs the question as to whether this portrait was intended to challenge the authority of the British government, perhaps particularly in relation to fiscal policy (the RBS bank note being very visible). Also visible are two pistols (which had also been proscribed); a further challenge to the government.