The value of reconstructing historical clothing

Reconstructing historical dress, for me, is more than a passion; it is a window into the past. Every stitch and each decision made in the making of a garment pulls me deeper into the past. It allows me to connect not only with the people who wore these clothes but with those who made them—people who, more often than not, remain invisible in the historical record. For someone like me, whose roots lie in generations of textile workers and artisans, this work is more than academic. It is personal. It is about understanding the skill, precision, and artistry that shaped the lives of my ancestors, and learning how that legacy lives on in my own hands.

Burning the midnight oil at Nunton House, Benbecula in 2023 while working on the Betty Burke project.

Reconstructing a historical garment is like learning a new language. There is the grammar of cut and construction, the vocabulary of cloth and stitch, the dialects of regional styles and individual tailoring quirks. But the beauty of this language is that it is spoken through the body. When you wear a reconstructed gown or waistcoat, you do not just see history—you feel it. You stand differently, move differently, you can even think differently. And with that shift comes understanding – an embodied understanding. It is an experience that can’t be gained from looking at portraits or reading written descriptions. It is what the scholar and practitioner in me craves: to feel history, quite literally, right next to me.

The Margaret Hunter Shop at Colonial Williamsburg, USA last summer

Few garments offer such a vivid embodiment experience as stays. These structured undergarments are central to 18th century women’s dress, and they are among the most fascinating pieces to make. When I construct stays by hand, the process takes me around two full-time weeks of work—each stitch carefully placed, each boning channel aligned, each panel shaped for support. It is slow, demanding work, but immensely rewarding. There is a kind of intimacy in making something so foundational to a woman’s daily life in the period. And what I have learned through this process has reshaped my understanding of women’s history in ways I could never have gained from observing stays behind glass.

Constructing stays by hand

Wearing stays myself—albeit briefly—has shown me how dramatically they alter the body’s carriage, and how misunderstood they often are. If made correctly, stays are not restrictive at all. In fact, I find them more supportive and, surprisingly, more comfortable than many modern bras. But unlike the women of the 18th century, I did not grow up wearing them. After a day in stays, I am ready to take them off. For women of that era, however, these garments would have been second nature, shaping not only their bodies but their movements and expectations from an early age. That kind of ingrained physical experience is impossible to replicate, but I come closer to understanding it with every set of stays I make and wear. It is an education that needle and thread (along with beeswax, thimbles and pliers!) have given me in a way no book ever could.

What we choose to wear—even today—is never meaningless. Sartorial choices are loaded with information: class, politics, geography, trade, even mood or intent. Clothing is often the first thing someone notices, and historically, it was a quick and powerful visual reference. Was someone rich or poor? Protestant or Catholic? A Highlander or a Lowlander? You could tell by the style, the cloth, the cut, the colour. In a time when literacy was not universal and photographs did not exist, what people wore was one of the most direct ways of reading who they were—or who they wanted to be. That kind of visual storytelling fascinates me. And when I reconstruct historical dress, I try to think not only about what a garment looked like, but what it communicated.

This is clearest in the way monarchs have historically tried to control dress. Sumptuary laws—rules about what people could or could not wear—existed for centuries across Europe, reinforcing social hierarchies through fabric and fashion. In Scotland, after the Jacobite Rising of 1745, the British government passed the Act of Proscription (1746), which made it illegal for Highland men to wear traditional Gaelic dress, including tartan and plaids. Clothing itself became a political act. To wear Highland dress was not just to express identity—it was, quite literally, to risk imprisonment. That is how powerful clothing can be. It can unify, defy, or endanger. When I recreate garments from this period, I think of that: how deeply woven clothing is into our histories of power, resistance, and belonging. And that is where tartan’s link with rebellion comes from.

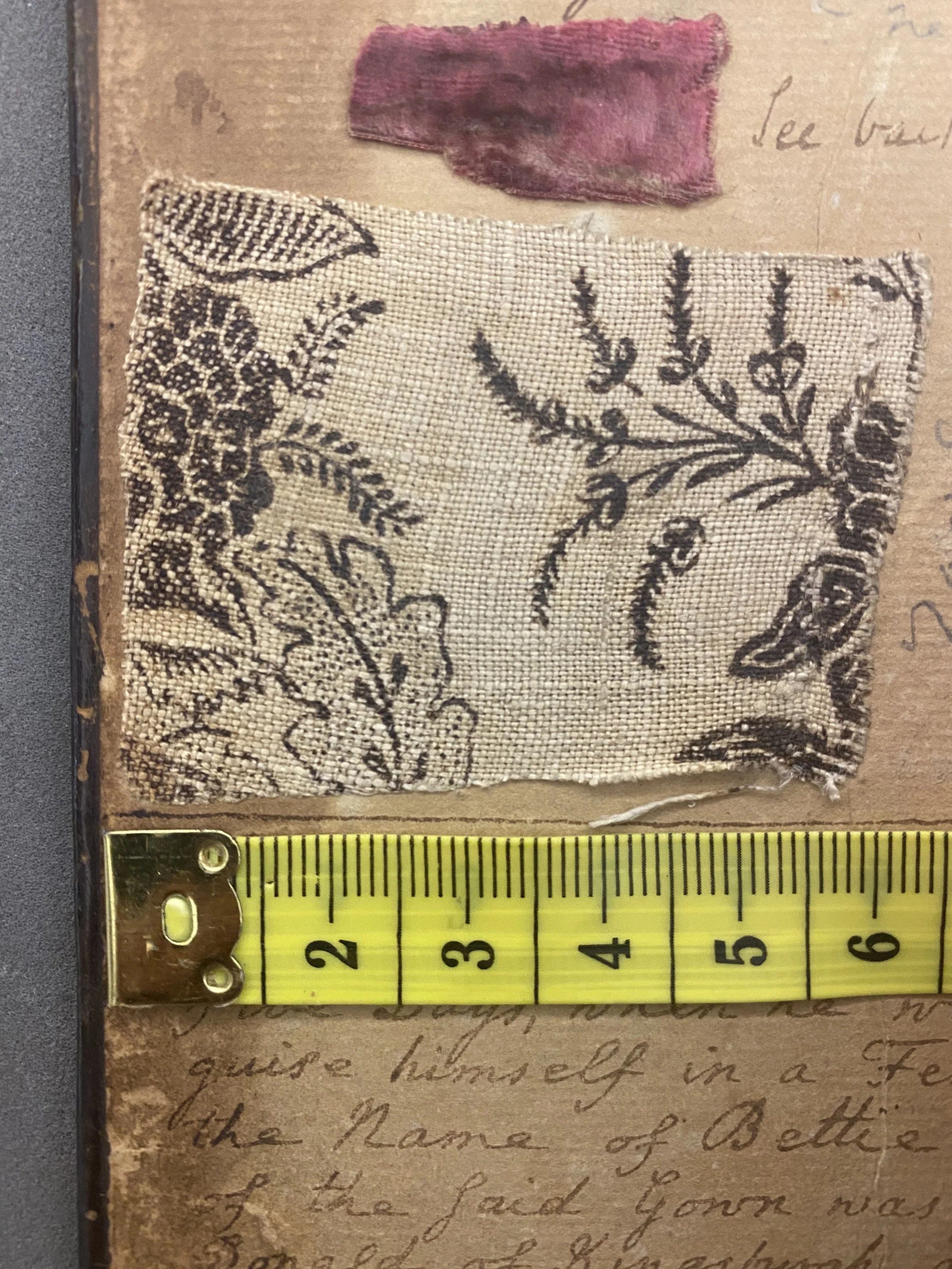

After 16th April 1746, and the disastrous end of the Jacobite Rising at Culloden, Prince Charles Edward Stuart—Bonnie Prince Charlie—was a fugitive. On the run from the British army, he disguised himself as an Irish spinning maid named Betty Burke to escape to the Isle of Skye with the help of Flora MacDonald. The outfit he wore during this flight included a printed cotton calico gown and an Irish manle. Remarkably, a small piece of the original printed linen calico survives along with a snippet of apron string, a snippet of the prince’s blue silk garter, an original piece of Kingsbugh tartan and red stuff all worn by Charles Edward. These precious textile fragments ar not housed in a grand display or encased in glass, but are rather affixed to the inside cover of the original Lyon in Mourning manuscript, held in the National Library of Scotland.

The pattern was digitally recreated using high-resolution images and was then reprinted onto fabric. I set about reconstructing the gown Charles would have worn in disguise at exactly the same place the original was made by Flora Macdonald and Lady Clanranald 277 years previously - Nunton House on the island of Benbecula. I was there the same week that the original was made and that in itself afforded me some useful insights. For example, it was possible to sew long into the night as it only gets dark for a few hours during the summer on the island as it’s so far north. That explained how the ladies were able to reconstruct an entire outfit in just four and a half days. The dress itself was easy to make - it’s a simple garment which only took me two days - but its story is anything but.

The Irish cloak was such an excellent disguise. Amazingly our model here could see perfectly where he was going although his face was almost entirely shielded from view.

This was a prince in hiding, crossing hostile territory, relying on his clothes not for ceremony or status, but for protection. The clothes helped save his life. Recreating them helped me understand not just the man and the myth, but the very fabric of rebellion, survival, and subterfuge. It also made me think deeply about the women who made the clothes (away from their servants so they would have plausible deniability) and how much stress they must have been under sewing the gown, bonnet, apron and adjusting the petticoat and cloak.

One of the things I love most about historical dress: it collapses the space between the extraordinary and the everyday. When I recreated Flora MacDonald’s wedding dress—another project rooted in 18th-century Scottish history—I was not just paying homage to a famous historical figure. I was also engaging with the lives and techniques of women like Flora who created, wore, and maintained these garments themselves. For this dress, I worked closely with a master weaver to recreate the tartan for the arisaid, and then drafted the pattern directly on the body, just as it would have been done at the time. There is something incredibly intimate about that process. No paper patterns, no shortcuts—just me, the fabric, and the form. Each decision guided by hand and eye, as it would have been two centuries ago. We also used dye analysis of the wool fibres from the original piece of the tartan at the West Highland Museum which not only gave us a date of between 1747 and 1752 (Flora got married in 1750) but also a location of production (the Hebrides), merging scientific fact with archival material and my own creative skills.

Most recently, I have been working on a reconstruction of Sir John Hynde Cotton’s trews, held in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland. They are a fascinating survival—one of very few extant examples of 18th-century trews. My work has been guided by a brilliant article written by former NMS curator Helen Bennett in the 1980 issue of Costume journal, which included a scale pattern of the trews. Using that as my foundation, I recreated the garment entirely in just five part-time days. Once the pieces are correctly cut, the construction is surprisingly straightforward. It is a reminder that while some historical garments appear complex, others—particularly those made for function and everyday wear—rely on a kind of elegant simplicity.

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s trews at the West Highland Museum. When I look at extant garments from the 18th century, I always feel better about my stitching because the originals weren’t perfect either!

In preparing for this project, I also studied the trews attributed to Bonnie Prince Charlie at the West Highland Museum. What struck me immediately was how closely their construction mirrored the Hynde Cotton pair. From the way the seat is cut to the angle of the inner leg seams and the finishing of the waistband, the similarities were striking. These were not isolated tailoring decisions—they were part of a wider tradition. Seeing this kind of continuity across garments worn by very different men, in different contexts, offers a tangible insight into 18th-century tailoring practices and regional dress. These pieces speak not just to individual histories, but to broader patterns of design and craftsmanship that connected people across Scotland and beyond.

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s waistcoat at the Clan Cameron museum. The entire garment is exquisite, but I think it’s the stunning metal galloon lace which I find the most fascinating. You just can’t get it made today. The skills which went into weaving it were phenomenal.

These projects do not just tell me about the clothes people wore—they reveal the astonishing skill that went into their making. Time and again, I find myself stunned by how advanced certain fabrics and techniques were. Whether it is a finely spun linen shift or a silk brocade waistcoat with perfectly matched seams, the level of artistry and technical knowledge embedded in these garments is breathtaking. And when I think that many of these items were produced by craftspeople whose names we will never know—often women, often working-class—I feel an even greater responsibility to honour their legacy. This, too, is where my family history plays a part. I come from long lines of weavers, dyers, seamstresses, tailors and milliners. Their knowledge lives in my DNA. And through reconstruction, I get to keep learning from them.

There is a misconception that historical dress is static and is frozen in time. But clothing is inherently dynamic. It was made to move. That is why the act of wearing reconstructed garments is so important to my work. It is through wearing that I come to understand how clothes shaped posture, gesture, and daily experience. Stays cut a little too high under the arms would change the way you carry yourself. A heavy wool skirt alters your gait. Even a tight-fitting sleeve might affect how you reach for something. These are small physical insights, but they add up to a fuller picture of the lived past.

In a world dominated by fast fashion, the slowness of historical reconstruction is a gift. It reminds me that clothing once carried deep meaning. Fabrics took a very long time and a lot of skill to make. They were valued, reused, refashioned. A sleeve might live three lives; a hem might be unpicked and redone. There was a respect for material that we could learn from today. Historical dressmaking, in its resourcefulness and longevity, has much to offer to contemporary conversations about sustainability and ethical fashion.

Reconstructing historical garments allows me and other dress historians to ask questions—and sometimes, to answer them in ways no textbook ever could. What did this feel like to wear? How did it move? What did it mean to the person who put it on each morning? These are questions about history, yes—but also about the human experience. About identity, belief, resilience, and expression. Every garment is a story. And when we reconstruct them, we are not just recreating clothing. We are reviving voices. We are recovering knowledge. We are remembering.

So, when I sit down with fabric and thread, with a fragment of the past in hand and the ghost of a seam to follow, I do not feel like I am working in isolation. I feel surrounded—by the people who wore these clothes, by those who made them, by the artisans in my own lineage, and by a wider community of makers, historians, and curious minds. Stitch by stitch, I piece together a patchwork of time, skill, and spirit. And in doing so, I find myself not only closer to history, but more deeply rooted in my own story too.