Isabella MacTavish, Malcolm Fraser and a certain tartan wedding gown (part one)

A few years ago, 2019 to be precise, I wrote a dissertation on Isabella MacTavish’s wedding gown.

Front cover of the dissertation

I got a distinction for it, as well as for the degree over. I’m incredibly proud of that fact. I’ve been reluctant to share the research I did on this project but my friend Abigail put me right on that this morning, so here I am sharing it ;-) What follows is cut and paste, then edited from my dissertation.

I’ve widely shared my dissertation by email free of charge since 2019, and it is in the libraries of UHI Sabhal Mòr Ostaig and the Highland Folk Museum for anyone who wants to reference it.

I should mention that there is chronological ordering to the topics, because this makes sense given the overall theme.

I think I’m going to expand on research into drugget skirts at some point, because researching the working class appeals more to me than the upper classes, although this is a challenge as there is little written evidence and only a few drugget skirts survive.

My dissertation’s abstract

And the contents page

Introduction

The clothing of Highlanders has been a source of fascination for both Scots and those from further afield for centuries. It has been written about by travel writers since they first started visiting the Highlands in the eighteenth century and publishing their journals. It has been written about in general volumes on dress, European dress, British dress and Scottish dress. The stereotype of traditional Highland dress is the male Highlander in a kilt or plaid. Quye and Cheape’s 2008 article on the earrasaid was ground-breaking in the way it analysed and discussed a particular item of female Highland clothing (Quye & Cheape 2008). However, there is still a lack of information on the clothing of female Highlanders which proves why this dissertation is required to fill some of the gap.

This dissertation starts by discussing dress which was worn in 1785, and is often described as traditional female Highland dress, to provide a starting point into the evaluation of female Highland dress.

My love affair with Isabella MacTavish’s wedding dress started one evening when browsing through Pinterest and it popped up in an ‘Outlander costumes’ Pinterest search. I was captivated by the dress, looking at the image almost every day for a week before I started to read about the dress itself and then more widely about 18th century Highland dress. It is the image on the title page which lead me on to purchase a second-hand copy of John Telfer Dunbar’s The History of Highland Dress, and the TV programme Outlander which sparked my interest in 18th century Scottish history and created a desire to know much more.

Isabella MacTavish was born at Ruthven in Stratherrick, Inverness-shire on 3rd January 1760 and was baptised there on the following day, 4th January 1760 (OPR Births 096/A 10 21 Dores). Her parents were John MacTavish and Anne MacKenzie, who were both servants to William Fraser of Balloan at the time of their marriage on 4th June 1753 at Ruthven (OPR Marriages 096/A 10 98 Dores).

It is highly likely that Isabella grew up as a native Gaelic speaker and that she also learned to spin yarn as a child. Ruthven was a part of the forfeited estates of Fraser of Lovat. A census of the forfeited estates was conducted in 1755/56 and shows that the 27 inhabitants of the township only spoke Gaelic (with the exception of the Frasers of Balloan who spoke both Gaelic and English) and that all women in the township knew how to spin, which included Isabella’s mother, Anne MacKenzie (SRO: 1973). [Isabella would have therefore been known as Isebail nic Iain; Isabella, daughter of John. She might have had another nickname as well, as was common in the Gaidhealtachd (and still is today in the Western Isles)].

She married Malcolm Fraser, from the nearby farm of Bochrubin, on 12th January 1785 at Ruthven (OPR Marriages 096/A 10 112 Dores). The family strongly believes that she wore this dress for her wedding, that she spun the yarn herself for the dress and that the linen was spun by her from flax grown at Ruthven.

Linen lining inside the bodice with lacing holes. I dread to think of how many hours it took to produce this fabric, from sowing of the seeds to the sewing of the bodice.

The dress and accompanying plaid are made from approximately 9.5 metres of single width hard tartan (which varies in width from 64.05cm – 65.5cm) and linen with about 1.5 metres of single width linen twill fabric.

Collage of photos I took of the dress in February 2018, when I first examined it at the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery. As you can see, it wasn’t professionally sewn, although the stitches are relatively even and fit for purpose.

[Thanks to the generosity of the family,] The dress and plaid have been on display for most of the twentieth century and all of the twenty-first century, and on permanent display at the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery since 1984 (except for family weddings) and it featured in the National Museum of Scotland’s Summer/Autumn 2019 exhibition, Wild and Majestic. [and since then in the Tartan exhibition at V&A Dundee, 2023/4].

Collage of direct descendants wearing the dress and plaid at their weddings (and dressing up!)

Previous research

Tartan expert Peter MacDonald has previously surmised that the dress was made from an old plaid woven in the 1740s -1760s and that this indicated poverty:

“What has been missed by those who previously studied the costume is the fact that that [sic] it was made from and [sic] old plaid or plaiding material and that the cloth itself is probably considerably older than the dress and possibly dates to c1740-1760. As such, this is the only known surviving example of such a reuse and gives us an insight into the thrift and relative poverty of the average Highlander compared to the gentry in 18th century rural Scotland.” (MacDonald, 2014:1)

Emily Taylor, Assistant Curator at the NMS, also wrote an interesting article which hypothesised that the dress dated to the 1750s due to some elements of the style of the dress - the width of pleats of the en fourreau back and the sleeve cuffs are more typical of the 1750s than 1785- stating that:

“The comparisons connect the dress’s style beyond the Highlands, demonstrating the wearer as conscious of contemporary fashion outside of their immediate locality.” (Taylor 2018: 220).

Searching for primary sources

By spending time in the archives at the National Archives of Scotland, I have discovered a good amount of information about Isabella’s life. She was born, married and bore her first children at Ruthven in the parish of Dores, not far from Loch Ness, which was part of the Forfeited Estate of Lord Lovat.

Ruthven had been wadset to William Fraser of Balloan, a son of Fraser of Culduthel (and brother to Major James Fraser of Castle leathers) in 1735 and we can thereby assume that he was a man of means who would not have had his female house servants wearing second-rate clothing.

I have tried unsuccessfully to find any account books relating to the family and therefore do not know the wages which Balloan paid to his servants, but it is not unreasonable to assume that their pay would have been adequate, that they would have been provided with a cottage in the township and that they would have had a fairly comfortable existence.

Dye analysis

In 2018, with permission of the owner, I commissioned textile dye analysis of the fibres. The use of chemical dye analysis was used very successfully by Hugh Cheape and Anita Quye during their research while at the National Museum of Scotland (e.g. Quye and Cheape 2008), and provides irrefutable scientific fact.

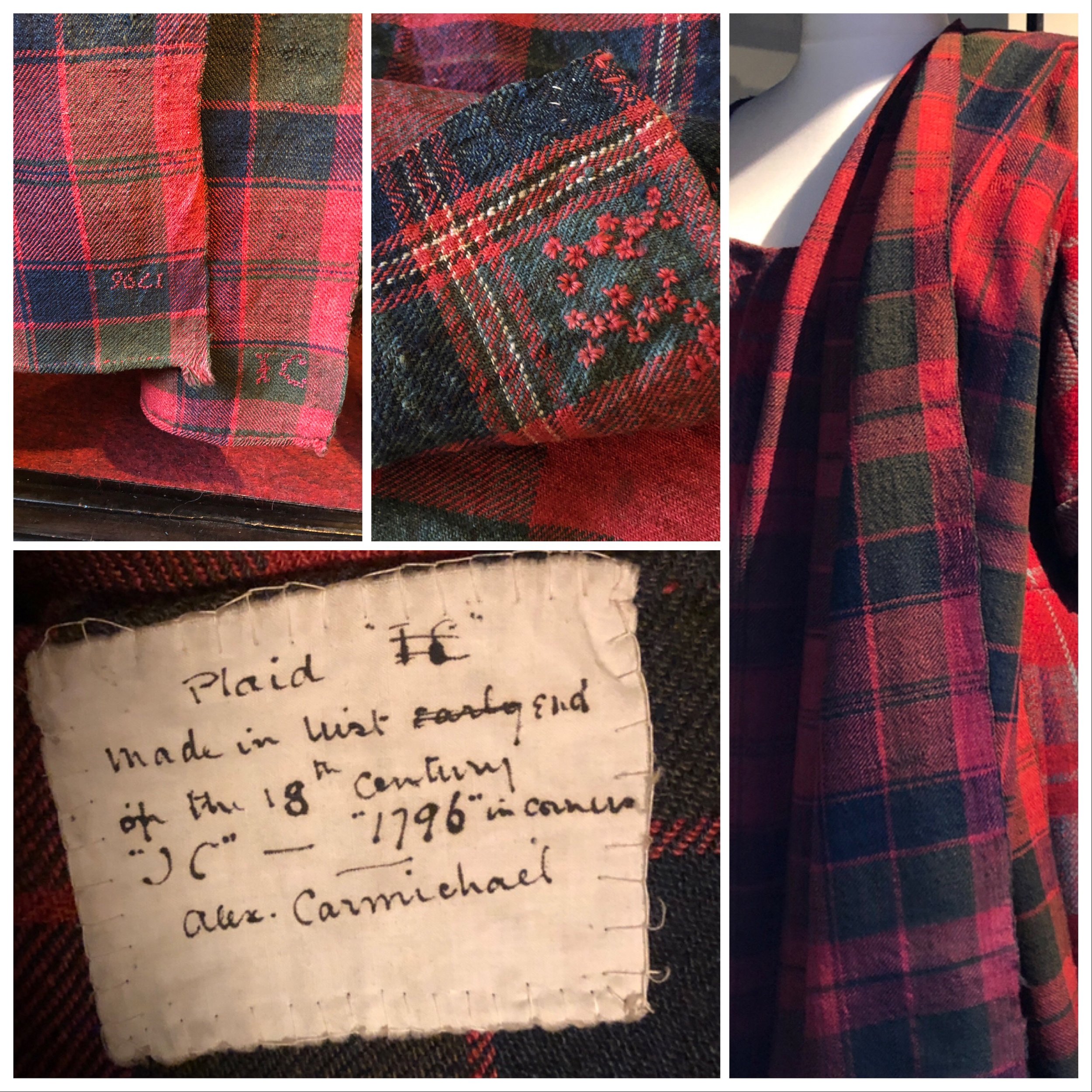

Threads from Isabella’s plaid, taken with full permission of the owner, at the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery in late 2018.

The results of the dye analysis demonstrate that

cochineal dye was used for the red dye,

indigotin (probably indigo and not woad) was used for the blue and a

combination of indigotin, old fustic and quercitron for the green.

Due to the use of quercitron, the fabric can be accurately dated to after October 1775, which is when it was first imported into Britain by the entrepreneurial Edward Bancroft, who discovered quercitron as a fast yellow dye and had a patent and 14 year monopoly on its sale in the United Kingdom issued by the UK parliament (Schaeper 2011: 44).

[After I published the dye analysis results on my former blog,] the National Museum of Scotland dated the dress to between 1775-1785 which ties in with the family’s belief that Isabella made the dress specifically for her wedding in either late 1784 or early 1785 and the availability of the dye quercitron.

IC’s arisaid at the West Highland Museum. Thanks to the fact that the glass is the cabinet has been treated to prevent UV damage, the dress is still on permanent display and you can see it today in Room 5 when you visit the museum.

First reproduction dress (early 20th century) and 18th century arisaid

There is an earrasaid dated 1796 in the collection of the West Highland Museum, collected by Alexander Carmichael in the Uists in the 19th century) which has the same dye content and also has the appearance of a homemade hard tartan (Cheape 1993:). I chose this earrasaid to go on display with a replica of Isabella’s wedding dress made in the early 20th century in Fort Augustus which I helped to conserve at the end of 2018.

Other items: Isabella’s ring and brooch

Isabella MacTavish’s wedding ring and luckenbooth brooch have also been passed down through the family as well with the dress and plaid. Stamps on the rear of the brooch indicate it was made in Inverness by Thomas Borthwick who was active in Inverness 1772 until 1783. They have both previously been on display with the dress and plaid, although they no longer are.

Isabella’s ring on the hand of her descendant, Isabel.

The back of the luckenbooth brooch. These sorts of brooches were traditionally used the same way in which we use engagement rings today, and most likely was given to Isabella by Malcolm at their bethrothal

A significant part of the story of this dress is its repeated use for family weddings by Isabella’s descendants – it was also worn in 1826, 1970, 2005 and the plaid only in 2018 – as well as the fact it has been on display for most of the twentieth century and all of the 21st century. This therefore means that the dress and accompanying plaid have become a very important marital tradition in the Fraser/Beaton family; however this dissertation will argue that while the tartan fabric used to make the dress is synonymous with the Highlands, and there is a continuing dress tradition of women wearing the plaid, the dress itself is not an example of traditional female Highland dress but rather a fine example of 18th century female dress, made in the Highlands.

And that is where I am going to leave it for today, but I am going to publish the rest of my dissertation on this blog in due course.