Tartan and ‘Highland’ dress

What follows is the next part of my dissertation; it is not my entire thoughts on the absolutely ginormous topic of tartan and Highland dress. If this is a topic you’re interested in, I highly recommend the excellent From Tartan to Tartanry which has lots on offer for you to think about (I’ll be uploading the bibliography towards the end of the wee series, but you should be able to find the book on a Google search. Sadly the last time I checked if the book was still in print, it was not but was available electronically.

Back to today’s blogpost. While it is not on Isabella and Malcolm, or her dress specifically, this wee section was written to set the study/ dissertation in some context. First, though, I thought it would be useful to explain what the rest of the dissertation is about.

The dissertation is split into three chapters. The first short chapter discusses the notion of tradition and the Gaelic view of it. The second chapter focuses on the first half of the long eighteenth century and discusses the Act of Proscription, which applies to male civilian Highland dress only but had a significant impact on Gaelic culture, contributing to the ‘pacification’ of the Highlands in the 1750s-1760s. It also offers a contrast to the sections which follow on female Highland dress. The third chapter focuses on female Highland dress in the second half of the long eighteenth century and finishes with a look at the drugget skirt which has not been studied before in any real depth.

A stock image (from Squarespace) of Loch Ness. Isabella spent her entire life within a few miles of the shores of the loch.

Location and timeline

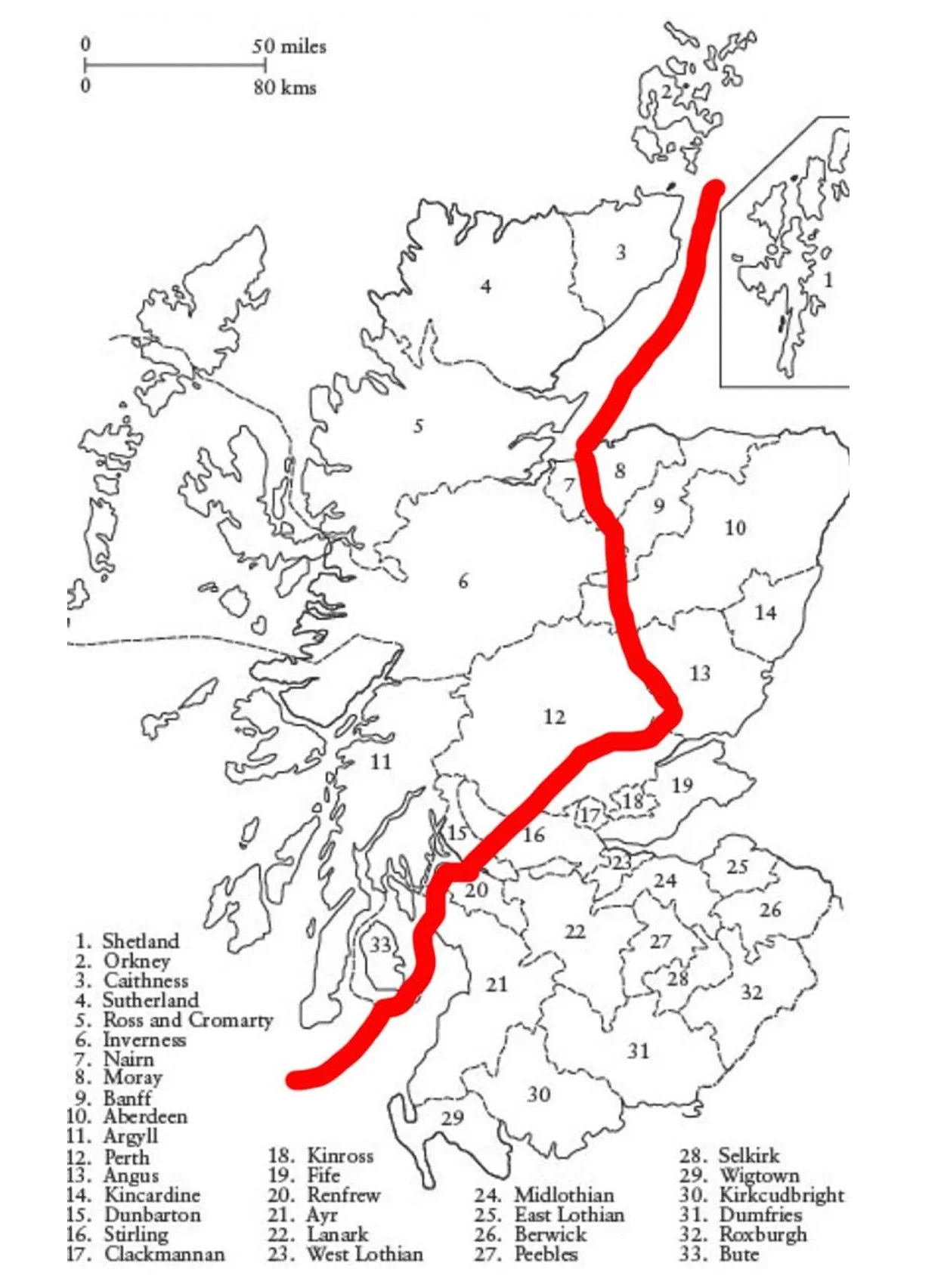

This dissertation looks at a specific area of Scotland – the Scottish Gàidhealtachd which included the counties west of the Highland fault line: Caithness, Sutherland, Ross & Cromarty, Inverness, Argyll and Bute (as well as Highland areas of Perthshire, Stirlingshire and Dumbarton) as shown on the map below on the and at a specific period of time – the long eighteenth century, defined by O’Gorman as starting in 1688 with the Glorious Revolution and ending in 1832 with the introduction of the 1832 Reform Act:

“To argue for a ‘long eighteenth century’ between 1688 and 1832 makes a good deal of historical sense. Most of the alternative dates, such as 1700 and 1714 at the beginning, and 1783, 1800 and 1815 at the end, are much less defensible. New centuries rarely mark new beginnings and 1714 establishes a new dynasty, not a new order. […] At the other end, the year 1815 marks the end of a massive period of warfare, not the dawn of a new historical era. Few new themes appear in the years immediately after 1815. It is true that the significance of the 1832 Reform Act can be exaggerated; historians now generally agree that those who framed it were more intent on conserving as much as they could of the old order. Nevertheless, the Reform Act was a sign that this old order was coming to a close.” (O’Gorman 2016: 2-3)

Map of the counties of Scotland in the long eighteenth century from O’Gorman (2016) with the Highland Fault Line drawn on top

The choice of location is two-fold; firstly this is the cultural region in which Isabella MacTavish lived, worked, died, made and wore her dress and secondly this is the cultural region I have studied the most during the MLitt in Highlands and Islands Culture. I will draw on things I have learned during the entire MLitt and most notably from the modules the Gaelic Legacy, the Tour of the Highlands and the Highlands and Islands Story (note: this MLitt no longer runs, sadly, but has been replaced by a wider Scotland MLitt on the same theme).

The choice of time period is mainly for practical reasons, namely there is not enough space in a Master’s dissertation to discuss female Highland dress from 17th century until today in the depth that it deserves; it is the period in which Isabella MacTavish was born, married and gave birth to 11 children (several of whom did not survive to adulthood) and it is the period of history in which life changed fundamentally for many reasons.

I aim to discover whether these fundamental changes were reflected in the clothing of Highland women during this tumultuous period and the reason for any changes. The early modern history of Highlands has been written as if no woman, other than Flora MacDonald, had ever lived there due to a focus on clanship and martial functions which have tended to marginalise the female experience (Nenadic 2001: 201).

The Gàidhealtachd had a strong patriarchal ideology which asserted male independence based on physical prowess and violence which praised the hunter-warrior chief as defender of the clan (Stiubhart 1999:233). There were also various taboos in Scottish Gaelic society on women’s activities (Reynolds, 2006: 174-175). For example, women did not receive training in the bardic traditions and panegyric poetry and were restricted to work-songs, cradle-songs and laments for self expression (Reynolds, 2006).

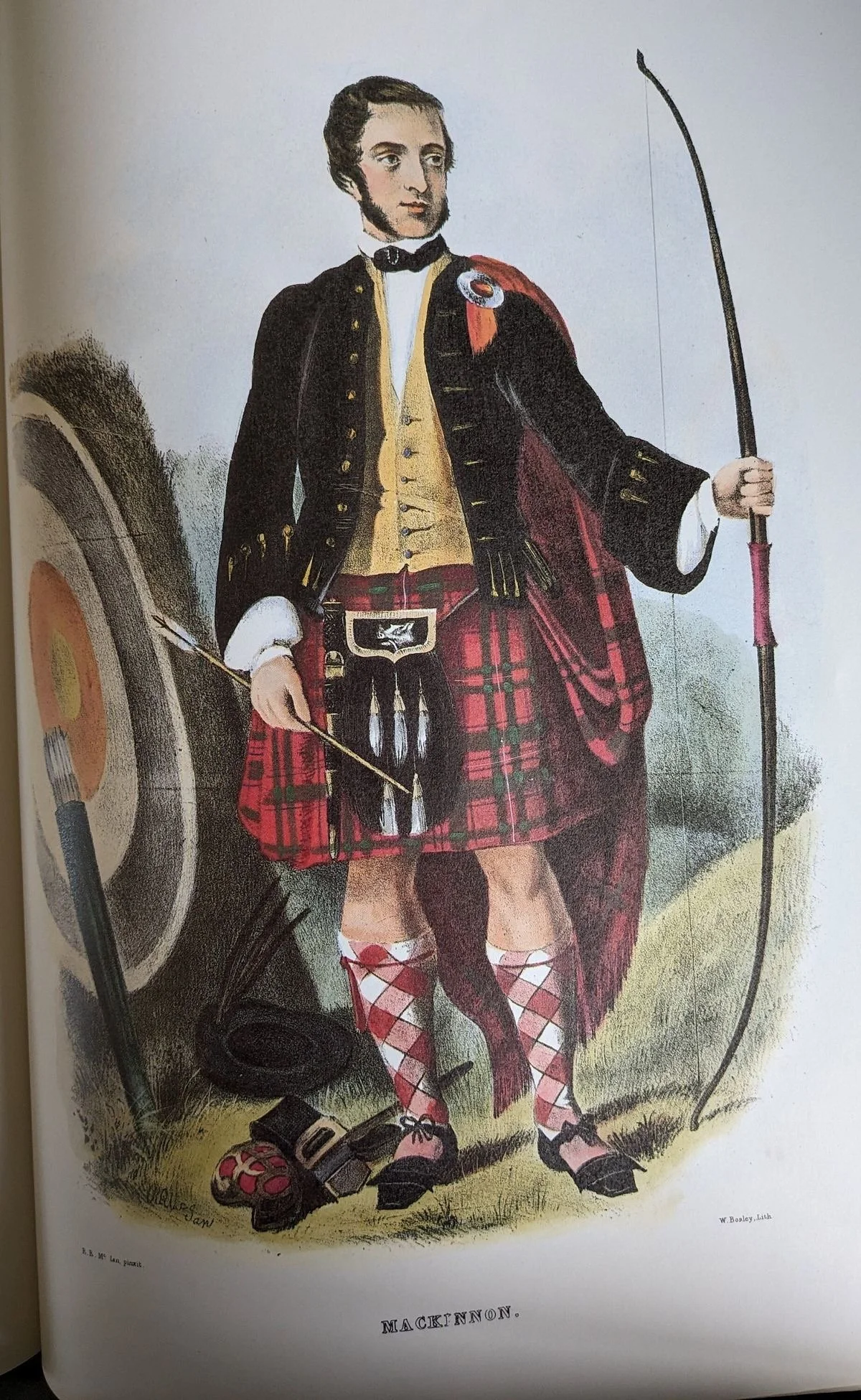

R R MacIan, Clan Forbes (originally published in 1845, my copy is from 1983. You can purchase them quite cheaply still on Abebooks). Sorry my referencing here is absolute pants; I’m not working at 100% this morning.

A few thoughts on ‘traditional’ Highland dress

What is commonly thought of today as ‘traditional’ Highland dress is a collection of clothing for men, which has never been the popular clothing of anyone except the British Highland Army regiments although the kilt does resemble the plaid which was popularly worn in the Gàidhealtachd before the Jacobite uprising of 1745 (Chapman 1995: 7-8.)

RR MacIan, Clan Forbes (from Logan’s Clans of the Scottish Highlands). The copy of the publication I have is from 1983, however I believe the original was published in 1845. It is probably one of my favourite books on Highland dress purely due to the fantastic Balmoralised view it presents of the history of Highland dress.

Although ‘traditional’ Highland dress has a kilted male as its stereotype, female Highland dress has its own history and significance, (Quye & Cheape 2008:1) John Telfer Dunbar’s 1962 book, History of Highland Dress, only contains twelve pages (out of 218) on female Highland dress.

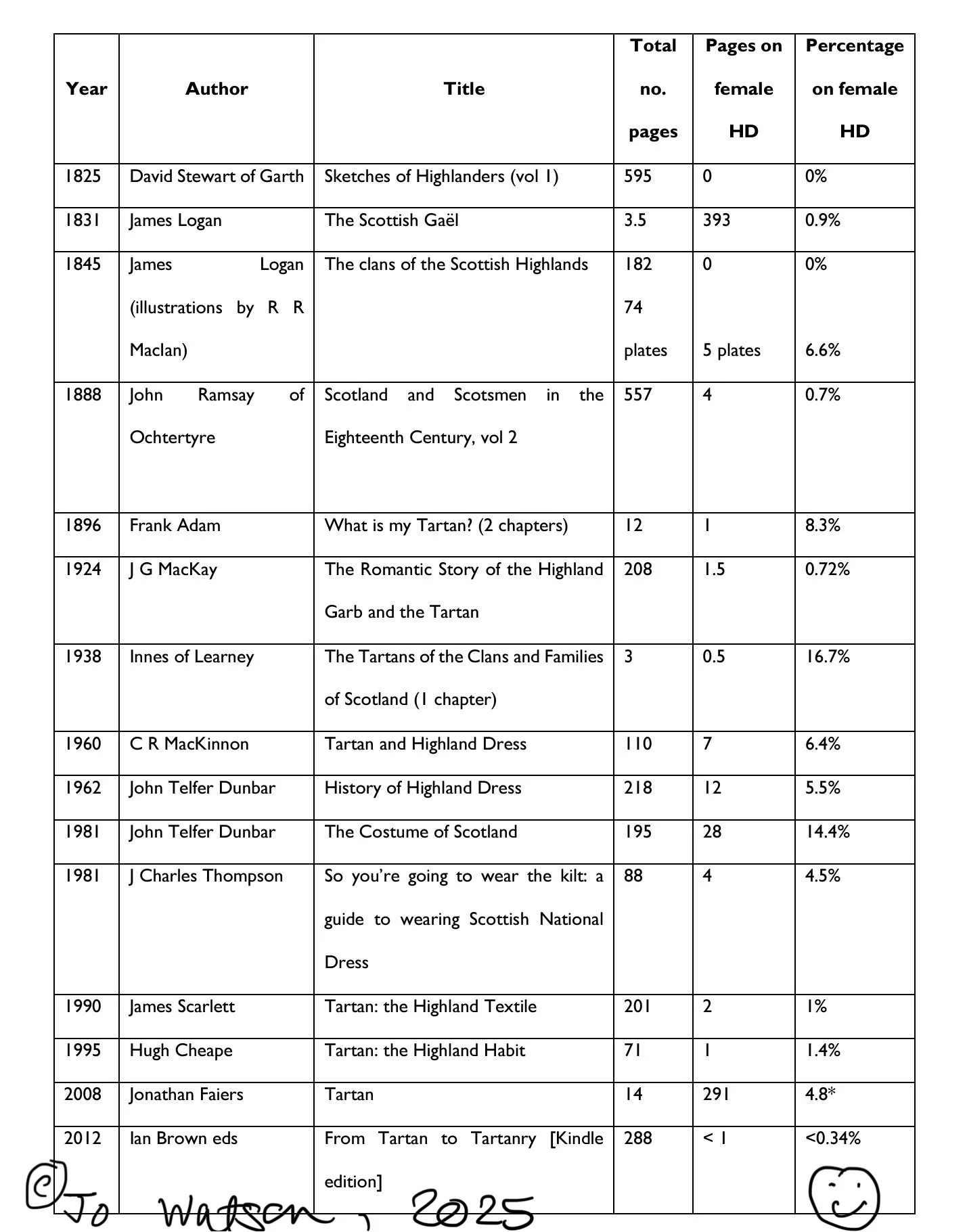

The absence of women in the discussion on Highland dress is not confined to Dunbar’s work alone. Below is a table containing information about some of the major works on Highland and Scottish dress and/or tartan which is presented to demonstrate how little attention has been paid to female Highland dress. The list is not exhaustive but does provide evidence of a large gap in information. The table clearly demonstrates that it is male Highland dress which dominates this discourse.

This table took me absolutely ages to compile. Please don’t be a dick and share it without my permission or take this information and pass it off as your own. I’m very happy for you to share it as long as you reference me in the correct academic manner. That goes for everything else on this blog, too. Thank you so much for understanding :-)

A Squarespace stock image for ‘tartan’. Thought it was appropriate here :-)

The role of tartan in Highland dress

“In terms of the material culture of dress and textiles, the historiography has been narrow and reductionist, seeking definitions of ever-receding ‘origins’ and bolstering defences against the assaults of detractors. Without exception, accounts of the history of tartan have largely ignored the voice of the devisers and wearers of tartan. […] [Tartan is] an indicator of belonging, now to the larger entity of nation but also to the smaller community of kin and clan, [and] these associations have led to an emphasis on, or more recently a fixation and obsession with, tartan as a badge or uniform of clanship.” (Cheape 2010: Kindle location 356-366/6575)

R R MacIan, Clan Mackinnon in Logan, James (1845) Clans of the Scottish Highlands. Can you tell yet this is on one of my favourite books?!

Scottish tartan, and its symbolism, has been written about extensively in the literature, however, it is important to mention it briefly here as it does play a significant role in Highland dress generally (and not just as the fabric used by Isabella MacTavish for her wedding dress).

Another Squarespace stock image of ‘tartan’. Very pleased to see the Watson tartan in the middle here!

Tartan has developed from a Highland craft to a mass-produced, globally consumed textile, which is an immediately recognisable symbol of a nation with a strong identity and has been worn as a badge of rebellion and non-conformity throughout history (Faiers 2008: 1-5). Tartan fabric is distinctive in colour, style and design and conveys personality, ceremony and drama (Cheape 1995: 3) and it can convey meaning better than many other sartorial designs (Brown 2012: Kindle location 195/6575).

Dress historian Sally Tuckett has argued that tartan and Highland dress have dominated the literature on historical Scottish dress and textiles which has resulted in their ‘intimate connection’ with contemporary Scottish identity (Tuckett 2010: i). She argues that this is a result of a growing sense of Scottish nationalism in the nineteenth century (Tuckett 2010: 2) and adds that: “Scottish history and the subsequent modern Scottish identity [are] the product[s] of many myths, a subject which has generated much discussion in itself. Highland dress and tartan are significant contributors to this combined notion of myth and identity” (Tuckett 2010:15).

As will be seen throughout the dissertation [or rather in future blogposts!] while tartan certainly does feature in female Highland dress in the 17th century and 18th centuries, and arguably in the ceremonial dress of the 19th – 21st centuries, there are other fabrics (such as drugget, silk and linen) which feature strongly in the dress of the women of the Highlands and Islands, and therefore a very strong focus on tartan is not warranted.

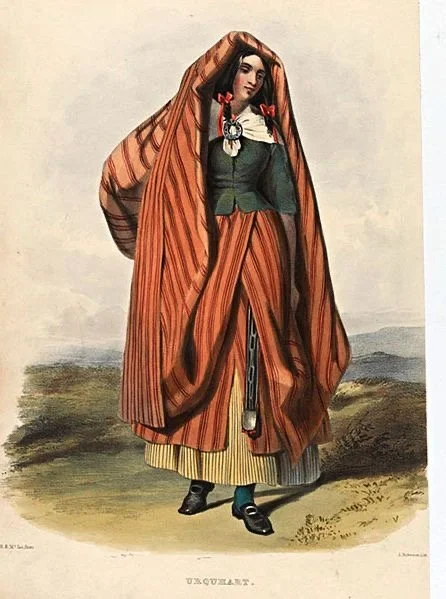

R R MacIan’s Clan Urqhuart. Yes, it’s depicting a woman. No, she’s not wearing tartan…

And neither is this lady. In MacIan’s world, both ladies wear striped woollen fabric, not checkered tartan fabric. I find this image absolutely fascinating; you’ve got a lady based on a 17th century description of female Highland dress (by Martin Martin), yet she’s got a mid 19th century boy holding on to her. I think I have figured out who the boy and the lady represent in MacIan’s thought process. Have you?